A Fresh Look at TypeScript

More and more people and projects are using TypeScript today! That’s interesting because in the world of JavaScript it’s not too common for a project’s use to accelerate years after it was released (2012).

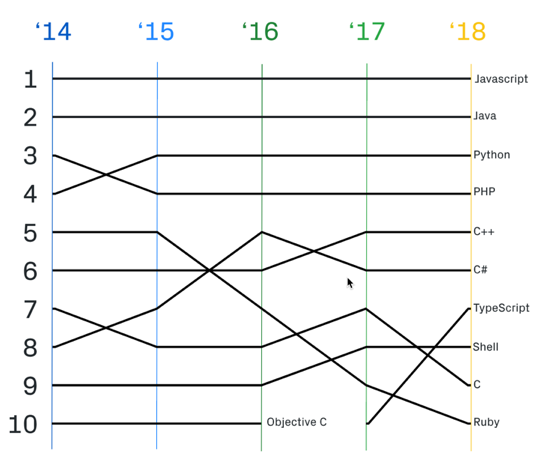

In the 2018 GitHub Octoverse Report, TypeScript reached “#7 among top languages used on the platform overall, after making its way in the top 10 for the first time last year”. It is also the #3 fastest growing language on GitHub.

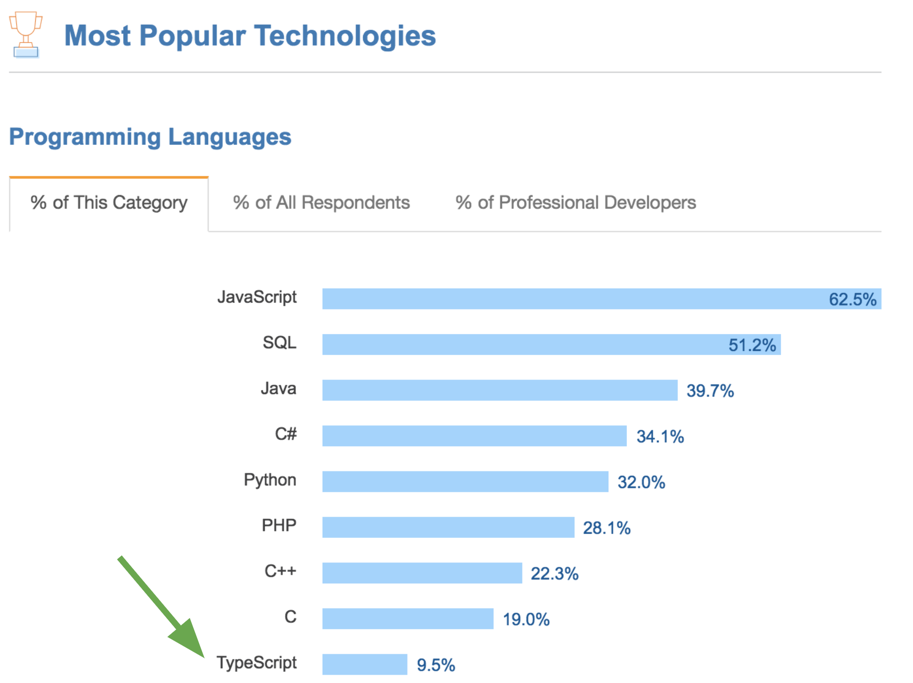

In the Stack Overflow Developer Survey Results 2017, TypeScript made the top 10 Most Popular Programming Languages list. In 2018, this category combined “Programming, Scripting, and Markup Languages” so if you exclude things like CSS, HTML, and Bash, it still made the top 10 in 2018. 😏

Birdseye View

At its core, TypeScript is superset of JavaScript that was designed by Anders Hejlsberg and initially released in 2012. It is made up of a language service and a type checking transpiler. The transpiler is run with the command tsc and takes TypeScript and converts it to JavaScript. The language service is a JavaScript based interface that development tools (think editors and CLI commands) can utilize to give development time support for things such as Intellisense, refactoring tooling, and symbol searching. Each of these parts are incredibly useful independently but when combined are even more powerful.

Notable Features

- Non-nullable type checking

- Implicit type checking

- Transpile async/await to ES5/ES3

- Implicit types (can be used for vanilla JS)

- ESNext (arrow, async/await, decorators, etc.)

- JSX support

Some Examples

Below, I’ll give some examples of how the type system in TypeScript can be used. This is certainly not an exhaustive list of features but ones I think demonstrate the power and usefulness of the language without getting too advanced.

Basic Types

The easiest part to understand of TypeScript is its type checking of basic types. In TypeScript, you use type annotations to describe the type of a parameter. In the following example, notice the person: string parameter. That : string suffix is the type annotation. You are telling TypeScript that only strings should be accepted as the person parameter on the greeter function.

function greeter(person: string) {

return "Hello, " + person;

}

var user = [0, 1, 2];

greeter(user); // ERROR: Argument of type 'number[]' is not assignable to parameter of type 'string'.A TypeScript error will be rasied when calling greeter(user); with an array of numbers because TypeScript knows person should only be a string.

Function Types

Functions in JavaScript are first-class objects and TypeScript has first-class support for type checking them. When specifying a function type, you can specify the type of parameters it has and also the return type expected. This is powerful. In the following example, we tell TypeScript that the save function takes a getUserId function paramter that must accept a string parameter and must return a number.

function save(entity,

getUserId: (username: string) => number

) {

let userId = getUserId(username);

}

save(entity, (username)=>{ // This anonymous function must match the type struture!

return 123;

});String Valued Enums

Enums are a bit foreign to the JavaScript world but it’s a shame because they make code readable and give static benefits. TypeScript brings them to JavaScript so you can do things like this:

enum Color {

Red = '#ff0000',

Green = '#00ff00',

Blue = '#0000ff'

}

const myFavoriteColor = Color.Green;

let chosenColor = Color.Red;String Literal Types

A fairly recent addition to TypeScript is something called String Literal Types. In the following example, the direction parameter of move expects a string, but not just any string. It must be “North”, “East”, “South”, or “West”. Passing any other string will cause a compile error!

type CardinalDirection =

"North" | "East" | "South"| "West";

function move(distance: number, direction: CardinalDirection) {

// ...

}

move(2, "North");

move(3, "Northwest") // ERROR: Argument of type '"Northwest"' is not assignable to parameter of type 'CardinalDirection'.Interfaces

Interfaces are really useful to provide a way to describe the shape of an object. You can even specify that properties are optional by adding a ? to the end of the property name.

interface Person {

firstName: string;

lastName: string;

age: number;

dob?: string; // Optional

}

let newPerson: Person = {

firstName: "Sue",

age: 24

}; // ERROR: Type '{ firstName: string; age: number; }' is not assignable to type 'Person'.

Generics

Generics are all about reusability. With them, you can design functions that are able to work with a type that is specified by a caller rather than hard-coded in.

class Queue<T> {

private data = [];

push = (item: T) => this.data.push(item);

pop = (): T => this.data.shift();

}

const queue = new Queue<number>();

queue.push(0);

queue.push("1"); // ERROR: cannot push a string. Only numbers allowed.Strict Null Checks

If you try to reference a property that could be null because to haven’t given it a value, TypeScript will error out. This is a huge deal to know this at build time!

interface Member {

name: string,

age?: number

}

getMember()

.then(member: Member => {

const ageString = member.age.toString() // ERROR: Object is possibly 'undefined'

})Decorators

Per the TC39 proposal:

Decorators make it possible to annotate and modify classes and properties at design time.

You can think of them as giving you the ability to augment or wrap functionality around other functions. Decorators are becoming standardized in JavaScript itself but have been supported in TypeScript for some time.

In the following example, we have a fetch method that we decorated with @protected. This allows to to run the protected function first, and then run the fetch function.

class PeopleController {

@protected

fetch(id){

}

}

function protected() {

if (!user.isAuthenticated()){

response.status = 403;

}

}